Location Analysis Process

- Identify types of real estate market data.

- Identify sources of real estate market data.

- Identify sources of property data.

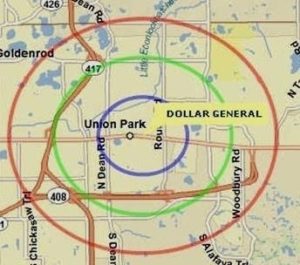

- Describe the basic features and benefits of mapping software.

- Apply statistical methods to market analysis.

- Recognize limitations inherent in gathering and using market data.